Political agendas need not be logically coherent, merely popularly seductive – Jonah Goldberg

Sunday, 8 March 2020

In the supermarket

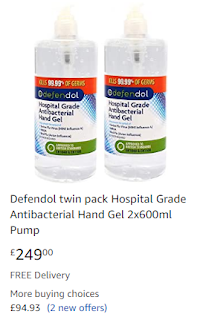

"Look at these empty shelves - it's all this panic buying there's hardly any soap left."

Proceeds to load up trolley with what's left of the soap - one, two, three, four.

Saturday, 7 March 2020

They promise too much

Only Truth can give

true reputation: only reality can be of real profit. One deceit needs many

others, and so the whole house is built in the air and must soon come to the

ground. Unfounded things never reach old age. They promise too much to be much

trusted, just as that cannot be true which proves too much.

Baltasar Gracian - The Art of Worldly Wisdom (1647)

Following on from the previous post, it is worth pointing

out that a media and entertainment organisation such as the BBC cannot possibly

be impartial. Impartiality is not and cannot be a major aspect of mainstream

media businesses. It is an ideal rather than some attainable state and in any

event the audience for impartiality seems to be far too small. For mainstream

media everything must be framed in a familiar way. The framing has to appeal to

both stakeholders and to an audience - it cannot be impartial.

To take a very simple example - in reporting the activities

of Greta Thunberg an impartial BBC would recognise that she exemplifies an

appeal to false authority. She is not an authority on climate change and her lack

of authority would have to frame all BBC reports about her activities. The

puppet’s strings would have to be visible.

A related problem affects enormous swathes of BBC reporting.

In general celebrities are not authorities on areas of life beyond their professional

expertise. This is not to say that outside opinions have no value, but celebrity

status rarely adds to that value. In world of mainstream media it obviously adds

value, but in an impartial world it would not.

In a similar vein, whenever a minister or shadow minister

makes some kind of claim, an impartial BBC would have to provide background

sources to the claim - no misleading omissions. It would have to find out who

advised the minister and on what basis that advice is deemed to be valid. Yet

this is probably not what BBC viewers actually want. They want the cut and

thrust of politics not the dull grind of impartial reporting. This is what the

BBC clearly wants too.

Another problem would arise from politically influential

people. An easy but powerful example has been provided by Jeremy Corbyn with

his long history of sharing platforms with political extremists and fanatics

who engage in or seek to justify political violence. Skating around Mr Corbyn’s

inglorious political history is not impartial.

The BBC generally claims to have an even-handed approach to

political debates, but even-handed is not the same as impartial. Mr Corbyn’s political

history would be a major factor in any impartial approach to many political

debates in the UK. It need not be an issue in the even-handed approach favoured

by the BBC. Even-handed can be and often is far less than impartial.

There is no particular need to labour these points because

the BBC quite obviously has a corporate culture and like all cultures it cannot

be impartial, otherwise it would not be a culture. This is the problem which has

to be tackled politically because the failings of the BBC are essentially

political. It purports to be more than it ever can be. As Baltasar Gracian

wrote over three and a half centuries ago They

promise too much to be much trusted, just as that cannot be true which proves

too much.

In which case the BBC has to evolve into a commercial

business because only this would allow it to be tolerably open about its

allegiances. As a media business it must project allegiances because it must

appeal to an audience with similar allegiances, an audience which is not and

never will be impartial.

Thursday, 5 March 2020

Can the BBC be cured?

From the BBC we are told of moves to cure it of something. Apparently it must "guard its unique selling point of impartiality" without having to admit that it isn't actually impartial. Oh well, it may be a step forward but it's a pretty hesitant one.

New UK Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden has said the BBC needs to do more to reflect the country's "genuine diversity of thought and experience".

Mr Dowden, who recently succeeded Nicky Morgan, made the comments in his first speech in the role on Thursday.

He also warned that the broadcaster must "guard its unique selling point of impartiality in all of its output".

And he questioned whether the BBC is "ready to embrace proper reform to ensure its long-term sustainability".

Trying to cure the BBC's cultural crony virus perhaps?

Okay I'll get me coat.

Mr Dowden, who recently succeeded Nicky Morgan, made the comments in his first speech in the role on Thursday.

He also warned that the broadcaster must "guard its unique selling point of impartiality in all of its output".

And he questioned whether the BBC is "ready to embrace proper reform to ensure its long-term sustainability".

Trying to cure the BBC's cultural crony virus perhaps?

Okay I'll get me coat.

Wednesday, 4 March 2020

Tell and tell again but never listen

Another weird piece from the Guardian -

It’s that time again in the political cycle, where some of the finest leftwing political minds in the country come together to scope out a coherent, principled and sellable policy on immigration, and roundly fail. As part of her Labour leadership campaign, Lisa Nandy, one of the brightest and least entitled Labour politicians of her generation, managed to pull off a remarkable feat – she made a pro-immigration position sound craven...

This fear of looking weak is why the opportunity to take on the Conservative party, and the right in general, by presenting a clear counter-narrative is missed again and again. There is already someone “listening” to people on immigration, already a party that has achieved the job of not making people feel irrational or racist for having anti-immigration views. Labour’s task is not to provide more of the same, but to spell out clearly the colossal trick that the right has played on the country, in taking the despair that should be directed at austerity, the gutting of the NHS, the corporatisation and dehumanisation of the state, and saying clearly that immigration has nothing to do with it.

Clearly immigration can be a problem if it is not managed in some pragmatic way which voters understand and generally favour. Acknowledging this politically is how democracy is supposed to work. There are caveats and limitations to immigration because there have to be and this is so glaringly obvious that even Guardian folk might be expected to see it. Apparently not.

Not really relevant but I'll admit to smiling at the political cycle, where some some of the finest leftwing political minds in the country come together. Not in the Guardian they don't.

I hope.

I hope.

Monday, 2 March 2020

Blimey who reads this stuff?

From the Guardian -

Until 2015, there were four main factional tendencies in the Labour party: the “old right”, the “hard left”, the “soft left” and the Blairites. The old right – rooted in local government and union bureaucracies – has campaigned against radical socialism since the 1940s. The political crises of the 1980s saw the Labour left divide between the hard left of Tony Benn and the soft left led by Neil Kinnock (and, later, Ed Miliband). The soft left wanted to update socialism for a post-industrial age, to expel Trotskyist factions from the party, and to make whatever accommodations it took to win elections. The hard left remained committed to the radical policy agenda developed in the 1970s, despite waning support for traditional socialism among the electorate. The Blairites, advocating free markets and globalisation, emerged as a distinctive section of the party elite in the 1990s, but never had an enthusiastic base among members; they always relied on support from the old right and the soft left to carry out their agenda.

Strewth - ideology certainly is a rum business. One might suggest that Labour

party selection committees could narrow down their list of plausible election candidates using a fairly

simple filter such as –

Don’t choose an ideologue – they frame things before understanding them.

Don’t choose a self-absorbed turd.

The two are not unrelated, but it isn't difficult is it? Yet I have an idea that simple little

mantras such as these do not drive the Labour party selection process.

Sunday, 1 March 2020

You know what freedom means

“You know what freedom

means.” But did he? Or, if he knew, had he got it? No, he had not got it. He

had had it possibly once, but now it had been stolen from him — stolen from him

by Bigges, who was pouring out champagne, stolen by the beautiful saddle of

mutton, the currant jelly, the crackling brown potatoes — stolen from him by

the cheque-book in his dressing-room table, the roses in the flower bowl, and

the electric wires that ran behind the boarding.

Hugh Walpole - Hans Frost (1929)

Freedom is a rum idea isn’t it? Whatever it is I don’t

think many people want it which at first sight seems an odd claim to put forward. Yet suppose freedom

is essentially the freedom to understand. In addition, suppose that for many people it is possible to

understand too much. This is one of the great historical criticisms of the

middle class – they don’t understand if it doesn’t suit them to understand. It is genuine too - they really don't understand. Or rather some do but that's a different issue. And as

the world becomes more and more middle class, perhaps this is a formidable flock of chickens finally coming home to roost.

For example, simple observation suggests that many folk have no wish to

understand aspects of their own ethos, especially fashionable

aspects which are supposed to be swallowed whole. Perhaps this still seems odd as an angle on freedom, but it appears to work

rather well. It fits well with censorship, attacks on free speech, forbidden

language and political attempts to hide, confuse and misdirect. All of these

are attacks on our freedom to understand.

Yet when we add up the constraints of daily life as Walpole’s character does, it is easy to conclude that we have no real

freedom anyway. On the other hand, the fact that we are able to think along

these lines suggest that potentially we do have freedom because we understand how

we could have behaved differently and the social effects of doing so.

Walpole's character knew that the beautiful saddle of mutton, the currant jelly, the crackling brown potatoes were trivial indicators of much wider constraints on his freedom. Merely rejecting the currant jelly wouldn't count for much when it came to wider questions of his freedom to think and act.

Walpole's character knew that the beautiful saddle of mutton, the currant jelly, the crackling brown potatoes were trivial indicators of much wider constraints on his freedom. Merely rejecting the currant jelly wouldn't count for much when it came to wider questions of his freedom to think and act.

Even so, freedom still seems to be a matter of paying close attention to our options and choices instead of freewheeling all the time. We

have to freewheel some of the time, perhaps most of the time, but not all the

time.

This is Spinoza’s key point about understanding things as they are including our own role in things as they are. Not things as they ought to be but things as they are. Observe and understand what is

going on, be truthful about it at least to ourselves and

be content with that. In this way we may come to understand how and where we could have responded differently

even when we didn’t. We may even understand why we didn't.

To my mind this is the great political divide, the one which cannot be bridged. There are those who try to understand themselves and their interactions with the real world and those who merely try to justify themselves. One leads to freedom and the other doesn’t. This seems to be why woke politics, the politics of political correctness is so bleak, repressive and totalitarian.

To my mind this is the great political divide, the one which cannot be bridged. There are those who try to understand themselves and their interactions with the real world and those who merely try to justify themselves. One leads to freedom and the other doesn’t. This seems to be why woke politics, the politics of political correctness is so bleak, repressive and totalitarian.

A diffuse divide as always, but still a divide. There are people who don’t want freedom and don’t

want anyone else to have it either. They know they can reject the currant jelly and that seems to be enough. It's as far as they choose to go.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)